project09:2025Msc2JIP: Difference between revisions

JIPStudent (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

JIPStudent (talk | contribs) |

||

| (16 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

=='''JIP 2025: Space Architecture & Robotics Group 1.13.1'''== | |||

=='''JIP: Space Architecture & Robotics'''== | ''This is a condensed summary of the final report; for the full final report, the problem statement and midterm reports, as well as all presentation slides, see the Documents section at the bottom of this page'' | ||

__TOC__ | |||

[[File:Render 4 Round 3 Horizontal.jpg|800px|frameless|center|Habitat under construction inside a lava tube]] | |||

More than 50 years after Apollo 17, space agencies are planning permanent human settlement on the Moon rather than brief visits. However, the lunar environment presents serious challenges, including frequent micrometeorite impacts, radiation levels up to 2200 mSv per event during solar flares and coronal mass ejections, temperature swings from 375 K during the day to 100 K at night, and moonquakes reaching body wave magnitudes up to 5 in shallow events. Numerous studies have proposed lunar outposts inside lava tubes, large natural structures 100 to 300 m in diameter formed by ancient lava flows, can shield habitats against radiation, meteorites, and thermal extremes. Some of these lava tubes are thought to be accessible via surface pits. | |||

Transporting payloads to the Moon costs approximately €1 million per kilogram, making heavy equipment like cranes or excavators impractical and human labor infeasible due to the need for temporary shelters and exposure to severe risks over an extended construction period. In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU) addresses this by using lunar regolith as building material, while autonomous robotic swarms with additive manufacturing can prepare a habitat ahead of crew arrival. Selective laser melting (SLM) of regolith is a promising technique for fusing material into structures without the need for additives. | |||

The 2025 Joint Interdisciplinary Project (JIP) Group 1.13.1 developed a conceptual design for an autonomous construction process leveraging in-situ construction using Selective Laser Melting and swarm robotics to construct a habitat in a lava tube. Two concepts were evaluated, prefabricated blocks and direct in-situ melting, with the in-situ melting approach selected for lower technical complexity and higher adaptability. The system employs robotic swarm construction techniques, using collectors that excavate regolith outside the tube, which also serve as depositors to transport and place processed regolith at the build site, processors that sieve material remove oversized particles, flatteners that ensure uniform layer thickness, and melters that fuse it around an inflatable substructure incorporating an airlock, which serves as both construction scaffold and final pressurized habitable volume. Powered by solar panels with battery storage, operations occur only during the 14-day lunar daylight period to avoid infeasible battery masses that would be required for continuous nighttime work, completing the process in approximately 2 years. The final structure is a structurally sound, radiation-shielded dome-habitat that is able to protect occupants from the harsh lunar environment. | |||

== Problem Statement == | == Problem Statement == | ||

While many concepts for lunar habitats have already been developed and proposed, these often fail to address many of the core challenges inherent to lunar construction. Some concepts rely heavily on the costly transport of large construction equipment/robots and additives from Earth, while others rely on the use of heavy ready-to-live-in modules. | |||

Therefore, the objective of this project is to develop an autonomous robotic construction process by leveraging swarm robotics and additive manufacturing. Ultimately maximizing the usage of in-situ resources, to construct a | |||

protective lunar habitat within a lava tube that can facilitate permanent human presence on the moon. | |||

== Objectives & Requirements == | |||

To realize the primary objective of autonomously constructing a permanent lunar habitat, the following objectives for the project were defined: | |||

* Outline a detailed step-by-step autonomous assembly process that meets structural requirements and the 24-month mission construction timeline. | |||

* Define and validate the complete ISRU process and required lunar regolith properties for optimal Selective Laser Melting (SLM). | |||

* Specify formal hardware requirements for all unique agents in the robot swarm including its solar-based power and wireless charging infrastructure. | |||

* Design a permanent habitat shell that provides a minimum internal livable volume of 120 m³ for three astronauts that maintains interior radiation exposure below 10 mSv per year. | |||

== Concept Development == | |||

To address the challenges of constructing a safe and sustainable lunar habitat, two alternative concepts have been developed within this project. Both approaches aim to exploit in-situ resources to minimize launch mass and enhance mission autonomy. | |||

===Concept 1=== | |||

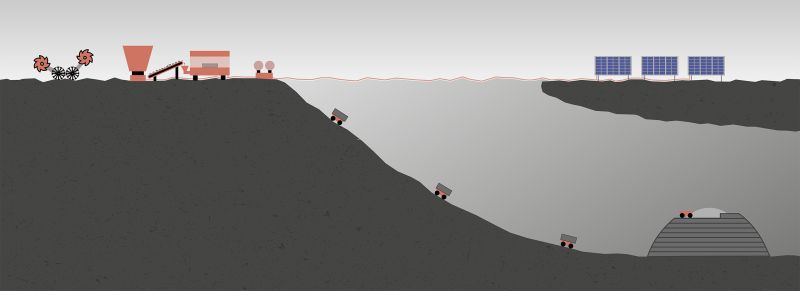

In the first concept, the structure is composed of modular blocks that are produced by static machines on the surface and later transported into the lava tube and assembled into a structure by a robotic swarm. | |||

[[File:JIP_Graphic_Concept_1_Cropped.jpg|800px|frameless|center|Concept 1 overview]] | |||

===Concept 2=== | |||

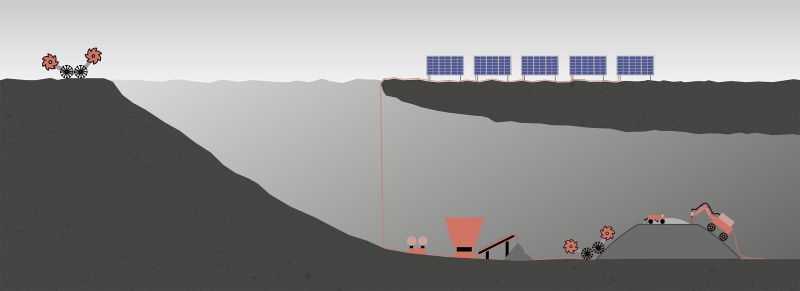

In this second concept, the structure is assembled in place by placing loose regolith layer by layer and fusing it together using a high-power laser; the material is partially melted, creating a composite material. | |||

[[File:JIP_Graphic_Concept_2_Cropped.jpg|800px|frameless|center|Concept 2 overview]] | |||

=== Additive Manufacturing Techniques === | |||

Three main additive manufacturing approaches for processing lunar regolith were evaluated in this study: Selective Laser Sintering (SLS), Selective Laser Melting (SLM), and additive-based methods employing chemical binders. The following subsections summarize their operating principles and assess their feasibility in the lunar environment. | |||

====Binder Based==== | |||

Additive-based methods mix lunar regolith with imported chemical binders or polymers to form a printable composite, enabling dense, mechanically stable structures. While effective for component fabrication, this approach requires a large amount Earth-supplied additives, undermining ISRU sustainability and increasing mission costs with each resupply. In the case of extrusion printing, equipment demands continuous operation to prevent binder solidification and clogging; interruptions necessitate full cleaning and waste material. In-situ binder production from lunar resources, such as water, adds logistical complexities without resolving maintenance risks, rendering the technique impractical for large-scale, long-duration lunar construction. | |||

====SLS==== | |||

Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) heats regolith particles just below melting point, fusing grains via surface diffusion without additives, achieving full ISRU compatibility. Its appeal lies in low material demands and energy efficiency compared to full melting. However, vacuum conditions produce highly porous structures with compromised mechanical strength. This inherent brittleness and reduced load-bearing capacity make SLS unsuitable for structural habitat elements. | |||

====SLM==== | |||

Selective Laser Melting (SLM) fully liquefies regolith into a vitrified, glass-like solid, minimizing porosity for superior cohesion and compressive strength (up to 125 MPa at 1500°C). Though energy-intensive due to higher laser power, it outperforms SLS in structural integrity without binders. Porosity can be further reduced via elevated temperatures or a second laser pass to release trapped gases. SLM was selected for its balance of performance and ISRU reliance, enabling robust, monolithic habitats despite scalability needing vacuum multi-layer validation. | |||

=== Concept selection === | |||

To evaluate the two concept a series of seven selection criteria where defined | |||

# Technical Complexity: number of subsystems and the difficulty to implement them in the lunar environment | |||

# Technological maturity and Risk: how much are the technologies involved in the concept developed and tested. | |||

# Adaptability: measures how modular and scalable the design is | |||

# Reliability and Maintenance: Measures the robustness of autonomous systems, their ability to continue functioning over time, and the ease of maintenance or replacement are therefore central considerations. | |||

# Structural Integrity and Durability: The habitat must not only stand structurally once assembled but also be able to withstand the lunar environment for a long period of time. This includes resilience against radiation, micro-meteorite impacts, seismic vibrations, and extreme temperature cycles. | |||

# Construction Time: Timely construction is important for mission planning and logistics. Assesses the total duration of the construction process, from regolith gathering to completion, and how effectively timelines can be accelerated by increasing the amount of construction equipment. | |||

# Logistical Cost: Launching material from Earth is the main cost driver of any space mission. This criterion focuses on the total mass that needs to be shipped from Earth to realize the concept. | |||

The | The seven criteria were assigned a weight using an Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP). | ||

Based on the evaluation across all criteria, Concept 2 emerges as the more favorable option for the mission objectives. Its lower technical complexity, higher adaptability, ease of maintenance, and stronger structural resilience under lunar conditions make it better aligned with the long-term sustainability and operational requirements of constructing a habitat in a lava tube. A key factor in this decision is cost, which carries the highest weight in the evaluation. Given the relatively low public interest in space exploration since the end of the space race, it is of utmost importance to provide a solution that is as cost-efficient as possible. A lower-cost approach increases the likelihood of delivering meaningful results within the current Artemis program budget and helps justify public funding, while also providing the potential to renew public enthusiasm for lunar exploration. Even though some private interest exists, it is likely that the first approach mission will be primarily agency-funded, making budget constraints a critical consideration for both policymakers and the public. Concept 2 is advantageous in this regard because it reduces the need for heavy, expensive SLM machines and eliminates the logistical and operational complexity of transporting and precisely placing pre-fabricated blocks, as required in Concept 1. Instead, it relies on smaller, modular laser-equipped robots to perform in-situ regolith melting, achieving similar construction goals with potentially lower costs and greater flexibility. Despite these advantages, the feasibility of large-scale regolith laser melting remains the most critical open question. Interviews with several experts have demonstrated that this technology shows promise. However, many challenges still remain before it can be applied on a large scale in a real lunar environment. In summary, Concept 2 offers the best balance between technical feasibility, operational robustness, adapt ability, and cost-efficiency, making it the preferred choice for the mission. As a result, subsequent development efforts and mission planning will focus on this second concept | |||

== Final Design == | |||

The habitat is a catenary dome with 20 m inner diameter, 120 m² floor area, and 556 m³ volume suitable for three astronauts. Built around an inflatable substructure that forms the pressurized volume, the shell uses a gradient voronoi infill (25% at base decreasing to 5% at top, averaging 15%) for material efficiency, with a thin unmelted regolith buffer protecting the inflatable during SLM. In total, the volume of the shell of the habitat will be roughly 220 m3 , resulting in a total mass of | |||

around 330 tons, assuming an average regolith density of 1,5 g/cm3. | |||

Melted regolith exhibits high compressive strength (18.4 MPa at a melting temperature of 1500°C) but lower tensile performance (16.3 MPa), necessitating the catenary shape to maintain loads primarily in compression while transferring part to the inflatable. For radiation protection, a minimum 54 cm wall thickness (with safety factor) reduces internal dose to below 10 mSv/y inside the lava tube, leveraging the natural shielding provided by constructing the habitat inside the lava tube, which lowers exposure by a factor of 40 compared to the surface. | |||

[[File:Final habitat design - section cropped.jpg|800px|frameless|center|Cross-section of the habitat structure]] | |||

== | ===Robotic Swarm=== | ||

The final design employs a diverse robotic swarm to autonomously construct the habitat shell via in-situ SLM of regolith. The system encompasses material handling for collection, processing and deposition, additive manufacturing for layer fusion , and support infrastructure with charging stations. | |||

=== | ====Collector robot==== | ||

The robot responsible for collecting lunar material outside of the lava tube is based on NASA’s IPEx concept. This 30 kg lightweight, battery-powered robot, equipped with two counterrotating drums, can collect and transport up to 30 kg of lunar regolith. This robot will also be used to precisely deposit the material required to construct each layer. Additionally, it will discard unusable material with a particle size > 2 mm at a designated location inside the lava tube. | |||

====Flattener robot==== | |||

the | This robot, called the flattener, is a 25 kg battery-powered machine designed to prepare an even layer of fine regolith for the melting process. It spreads out the deposited piles of processed regolith (with particles < 2 mm) and flattens it into a uniform 10 mm thick layer. Operating at a capacity of 50 m²/h, it ensures every layer is perfectly flat and ready for melting. | ||

The | ====Melting robot==== | ||

The laser melting robot is based on the GITAI Rover R1.5 platform. It features a long-reach robotic arm (almost 2 meters) equipped with a 1,5 kW laser, which is guided from a back-mounted box via a fiber-optic cable. The robot utilizes a tethered power connection for energy-intensive melting tasks and uses batteries for other operations. Its design supports modular tools and can also be fitted with a manipulator arm for setup procedures. | |||

==== Processing Machine==== | |||

A pair of stationary processing machines, located inside the lava tube, receive raw regolith delivered by the collector robots. Using centrifugal sieves, they separate the material into a fine fraction (0-2 mm) suitable for SLM and a coarse fraction (>2 mm) to be discarded. Buffers on either side of the sieve maintain a steady supply chain, allowing continuous operation even if deliveries are intermittent. | |||

The | ===Construction Process=== | ||

The habitat’s assembly is a sequential, 15-step process, organized into two primary phases: the preparation mission (steps 1-6) and the construction mission (steps 7-15). The initial phase focuses on establishing the necessary power and site infrastructure, while the second phase | |||

executes the deployment and autonomous construction of the habitat itself. | |||

=== | ====Preparation Mission==== | ||

Before construction of the habitat can begin, the site inside the lava tube must be prepared to ensure safe and efficient robotic operations. This phase starts with the deployment of fixed solar panels on the lunar surface near the lava tube entrance to capture sunlight and generate power. Power cables are then routed from these panels down into the tube, secured along the walls or floor to avoid interference with robot mobility. The power grid is tested for stability, including connections to wireless charging stations inside the tube that will keep the mobile robots operational. | |||

Next, the melting robots (equipped with removable scanning equipment) survey the designated build site. They map the terrain using onboard LiDAR and cameras to identify any irregularities, such as loose rocks or slopes. Assessment follows, evaluating floor flatness, ceiling height clearance for the final dome, and proximity to the entrance for material transport. If needed, the site is cleared: collector robots remove larger obstacles or excess loose regolith, transporting it to a waste area deeper in the tube. | |||

Finally, a detailed 3D digital twin of the site is created by scanning with high-precision instruments on the melting robots. This model serves as the reference for all subsequent construction planning, enabling precise layer deposition paths and real-time progress tracking against the catenary dome design. | |||

====Construction Mission==== | |||

With preparation complete, the core building phase commences. The inflatable substructure is deployed by melting robots using their manipulator arms and inflated to form the pressurized volume and initial support scaffold. Anchors secure it to the lava tube floor for stability. | |||

Collector robots then begin harvesting regolith from the surface, transporting loads into the tube and dumping them at the processing machines. The machines sieve the material, the fine fractions are kept while coarse waste is collected and hauled away by the same collector robots to the designated internal dump site. | |||

For each 10 mm layer, collector robots deposit piles of fine regolith in calculated positions around the inflatable, following paths derived from the digital twin. The flattener robots then spread and level the material into a uniform layer ready for fusion. Multiple units work in parallel to cover the dome's circumference efficiently. | |||

Melting robots, tethered for power, then scan the prepared layer with their lasers, selectively melting the regolith according to the gradient voronoi infill pattern; denser at the base for structural support, sparser toward the top for material savings. An unmelted buffer layer is maintained closest to the inflatable to prevent heat damage. Parallel melting operations accelerate the process, with robots coordinating to avoid overlaps or gaps. | |||

Throughout, the swarm maintains the site by clearing dust kicked up during deposition or flattening, using collector robots for removal. Periodic inspections via IR cameras on melting robots verify layer integrity, with the digital twin updated after each cycle. This layer-by-layer additive process continues until the full shell thickness is achieved, culminating in a sealed, radiation-shielded habitat. | |||

The | === Power Generation === | ||

The power generation requirements are primarily driven by the laser system. The total construction system requires an average of ≈ 30kW of power. This is mainly due to the energy demand of the laser robots, which each consume approximately 4 kW; 3 kW for the laser operation itself and 1 kW for supporting systems and basic functionality. | |||

The main power technologies traditionally used in space missions include solar arrays, fuel cells, and radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs). Solar arrays are lightweight and highly reliable, but their output is constrained by the lunar day and night cycle. Fuel cells can provide continuous power over shorter durations and were historically used in missions such as Apollo. RTGs, which convert radioactive decay heat into electricity, are widely used in deep-space missions where sunlight is scarce but are not suitable for missions that require big amounts of energy. More recently, renewed interest has turned toward compact nuclear fission reactors such as NASA’s Kilopower concept, which targets on the order of 10 kW per unit (Gibson and Oleson, 2017). Such systems could sustain robotic construction during the 14-day lunar night. However, their deployment is heavily constrained by regulatory concerns; in the event of launch failure, dispersal of nuclear material in the atmosphere and ocean remains a major risk. In this work, the selected baseline power architecture consists of solar arrays for power generation and batteries for energy storage. This choice prioritizes technological maturity, launch approval feasibility, and system reliability over the regulatory and risk barriers associated with nuclear systems. The dominant cost driver in such an architecture is the battery mass required to bridge the full duration of lunar nights while construction and excavation activities continue without interruption. Operating continuously through the entire 14-day night imposes a substantial storage requirement, whereas reducing or pausing activity during darkness could significantly decrease the needed battery mass and thus system cost. | |||

== | === Construction Time === | ||

A discrete-time simulation was developed to estimate the autonomous construction timeline, advancing second-by-second while modeling each robot as an agent with tracked battery levels, operational rates, states (working, traveling, charging, etc.), positions, loads, and maintenance. The process sequences through 380 layers, each requiring deposition, flattening, and melting phases in order, with parameters for 8 collectors, 3 depositors, 5 flatteners, 5 melters, processing at 150 kg/h (90% efficiency), and 8 charging stations under daytime-only operations (lunar nights impose hibernation, doubling calendar time). | |||

Results indicate approximately 6432 active hours (268 days) for productive work, extending to 1.48 calendar years when including night downtimes. Every layer requires roughly 17 hours to construct, with melting dominating (~68% of time), followed by deposition (~20%) and flattening (~12%); higher layers require less time due to reducing dome area. | |||

==Recommendations for Future Work== | |||

Future efforts should prioritize experimental validation of large-scale, multi-layer SLM in lunar-like vacuum conditions to confirm adhesion, porosity reduction (potentially via double-pass melting), and mechanical integrity of the monolithic structure, alongside sieving tests with diverse regolith simulants to verify 90% yield for <2 mm fractions. Structural modeling must address moonquake resilience up to magnitude 5.7, refining the catenary dome and voronoi infill for vitreous material fragility, while exploring alternative geometries and modular connections for expanded complexes. | |||

Mission architecture expansion should detail preparation phases and evaluate alternative power sources such as nuclear to enable continuous construction operations. This eliminates the need for hibernation periods during the lunar night, which can shorten timelines, and reduce long-term battery costs. However, while reducing night-time power usage to 1 kW is feasible during the robotic construction process, subsequent human habitation demands higher sustained power levels, making such drastic power limitation unfeasible post-construction. | |||

==Conclusion== | |||

This project has delivered a viable conceptual design for autonomously constructing a permanent lunar habitat inside a lava tube using in-situ SLM of regolith, overcoming key barriers to sustainable human presence on the Moon. By selecting the layer-by-layer in-situ melting approach over prefabricated blocks, the design achieves superior logistical efficiency, adaptability, and structural integrity tailored to the lava tube's protective environment. The 20 m catenary dome, with 556 m³ volume, gradient voronoi infill, and 54 cm melted-regolith shell, meets radiation limits (<10 mSv/y) and leverages compressive strengths (~125 MPa at 1500°C) while accommodating tensile limitations through shape and inflatable load-sharing. | |||

The robotic swarm of collectors/depositors, flatteners, and melters, executes the 15-step process fully autonomously. Preparation establishes solar infrastructure and a site digital twin; construction deploys the inflatable, processes ~327 tons of fine regolith, and builds layer-by-layer within 2 years under daytime-only operations. | |||

Daytime-only operation improves economic feasibility by minimizing battery mass (1,553 kg vs. 70,358 kg continuous), resulting in a total mission cost of €7.3 billion, a reduction of 90% compared to the continuous operations baseline, at the cost of doubling the total construction timeline. Construction of the habitat inside a lava tube reduces shielding needs (40× reduction compared to the surface), but moonquakes remain a big concern. | |||

SLM shows promise as a technology to use for the construction of the habitat, but future validation must prioritize large scale SLM performance in lunar conditions. Further research must be conducted regarding sieving yields, and moonquake-resilient modeling. Developing detailed robotic prototypes, advanced swarm coordination simulations, robust hibernation and dust-mitigation protocols, and investigating nuclear power for continuous operations, thereby shortening the construction timeline and supporting sustained crewed habitation, are all critical steps to advance from conceptual design to real-world deployment, ultimately enabling cost-effective, ISRU-maximized lunar settlement. | |||

== Documents == | |||

=== Reports === | |||

Final Report: [[https://moonshotplus.tudelft.nl/index.php?title=File:1.13.1_RoboticsInstitute_FinalReport_JIP2025.pdf PDF]] | |||

Midterm Report: [[https://moonshotplus.tudelft.nl/index.php?title=File:1.13.1_RoboticsInstitute_MidtermReport_JIP2025.pdf PDF]] | |||

Problem Statement Report: [[https://moonshotplus.tudelft.nl/index.php?title=File:1.13.1_RoboticsInstitute_ProblemStatementReport_JIP2025.pdf PDF]] | |||

=== Presentations === | |||

== | Final Presentation: [[https://moonshotplus.tudelft.nl/index.php?title=File:1.13.1_Space%26Robotics_FinalPresentation_JIP2025.pptx PPTX]] [[https://moonshotplus.tudelft.nl/index.php?title=File:1.13.1_Space%26Robotics_FinalPresentation_JIP2025.pdf PDF]] | ||

Midterm Presentation: [[https://moonshotplus.tudelft.nl/index.php?title=File:1.13.1_RoboticsInstitute_MidtermPresentation_JIP2025.pptx PPTX]] [[https://moonshotplus.tudelft.nl/index.php?title=File:1.13.1_RoboticsInstitute_MidtermPresentation_JIP2025.pdf PDF]] | |||

Problem Statement Presentation: [[https://moonshotplus.tudelft.nl/index.php?title=File:1.13.1_RoboticsInstitute_ProblemStatementPresentation_JIP2025.pptx PPTX]] [[https://moonshotplus.tudelft.nl/index.php?title=File:1.13.1_RoboticsInstitute_ProblemStatementPresentation_JIP2025.pdf PDF]] | |||

Public Poster Presentation [[https://moonshotplus.tudelft.nl/index.php?title=File:1.13.1_Space%26Robotics_PublicPoster_JIP2025.pdf PDF]] | |||

[ | |||

Latest revision as of 14:24, 18 November 2025

JIP 2025: Space Architecture & Robotics Group 1.13.1

This is a condensed summary of the final report; for the full final report, the problem statement and midterm reports, as well as all presentation slides, see the Documents section at the bottom of this page

More than 50 years after Apollo 17, space agencies are planning permanent human settlement on the Moon rather than brief visits. However, the lunar environment presents serious challenges, including frequent micrometeorite impacts, radiation levels up to 2200 mSv per event during solar flares and coronal mass ejections, temperature swings from 375 K during the day to 100 K at night, and moonquakes reaching body wave magnitudes up to 5 in shallow events. Numerous studies have proposed lunar outposts inside lava tubes, large natural structures 100 to 300 m in diameter formed by ancient lava flows, can shield habitats against radiation, meteorites, and thermal extremes. Some of these lava tubes are thought to be accessible via surface pits.

Transporting payloads to the Moon costs approximately €1 million per kilogram, making heavy equipment like cranes or excavators impractical and human labor infeasible due to the need for temporary shelters and exposure to severe risks over an extended construction period. In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU) addresses this by using lunar regolith as building material, while autonomous robotic swarms with additive manufacturing can prepare a habitat ahead of crew arrival. Selective laser melting (SLM) of regolith is a promising technique for fusing material into structures without the need for additives.

The 2025 Joint Interdisciplinary Project (JIP) Group 1.13.1 developed a conceptual design for an autonomous construction process leveraging in-situ construction using Selective Laser Melting and swarm robotics to construct a habitat in a lava tube. Two concepts were evaluated, prefabricated blocks and direct in-situ melting, with the in-situ melting approach selected for lower technical complexity and higher adaptability. The system employs robotic swarm construction techniques, using collectors that excavate regolith outside the tube, which also serve as depositors to transport and place processed regolith at the build site, processors that sieve material remove oversized particles, flatteners that ensure uniform layer thickness, and melters that fuse it around an inflatable substructure incorporating an airlock, which serves as both construction scaffold and final pressurized habitable volume. Powered by solar panels with battery storage, operations occur only during the 14-day lunar daylight period to avoid infeasible battery masses that would be required for continuous nighttime work, completing the process in approximately 2 years. The final structure is a structurally sound, radiation-shielded dome-habitat that is able to protect occupants from the harsh lunar environment.

Problem Statement

While many concepts for lunar habitats have already been developed and proposed, these often fail to address many of the core challenges inherent to lunar construction. Some concepts rely heavily on the costly transport of large construction equipment/robots and additives from Earth, while others rely on the use of heavy ready-to-live-in modules.

Therefore, the objective of this project is to develop an autonomous robotic construction process by leveraging swarm robotics and additive manufacturing. Ultimately maximizing the usage of in-situ resources, to construct a protective lunar habitat within a lava tube that can facilitate permanent human presence on the moon.

Objectives & Requirements

To realize the primary objective of autonomously constructing a permanent lunar habitat, the following objectives for the project were defined:

- Outline a detailed step-by-step autonomous assembly process that meets structural requirements and the 24-month mission construction timeline.

- Define and validate the complete ISRU process and required lunar regolith properties for optimal Selective Laser Melting (SLM).

- Specify formal hardware requirements for all unique agents in the robot swarm including its solar-based power and wireless charging infrastructure.

- Design a permanent habitat shell that provides a minimum internal livable volume of 120 m³ for three astronauts that maintains interior radiation exposure below 10 mSv per year.

Concept Development

To address the challenges of constructing a safe and sustainable lunar habitat, two alternative concepts have been developed within this project. Both approaches aim to exploit in-situ resources to minimize launch mass and enhance mission autonomy.

Concept 1

In the first concept, the structure is composed of modular blocks that are produced by static machines on the surface and later transported into the lava tube and assembled into a structure by a robotic swarm.

Concept 2

In this second concept, the structure is assembled in place by placing loose regolith layer by layer and fusing it together using a high-power laser; the material is partially melted, creating a composite material.

Additive Manufacturing Techniques

Three main additive manufacturing approaches for processing lunar regolith were evaluated in this study: Selective Laser Sintering (SLS), Selective Laser Melting (SLM), and additive-based methods employing chemical binders. The following subsections summarize their operating principles and assess their feasibility in the lunar environment.

Binder Based

Additive-based methods mix lunar regolith with imported chemical binders or polymers to form a printable composite, enabling dense, mechanically stable structures. While effective for component fabrication, this approach requires a large amount Earth-supplied additives, undermining ISRU sustainability and increasing mission costs with each resupply. In the case of extrusion printing, equipment demands continuous operation to prevent binder solidification and clogging; interruptions necessitate full cleaning and waste material. In-situ binder production from lunar resources, such as water, adds logistical complexities without resolving maintenance risks, rendering the technique impractical for large-scale, long-duration lunar construction.

SLS

Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) heats regolith particles just below melting point, fusing grains via surface diffusion without additives, achieving full ISRU compatibility. Its appeal lies in low material demands and energy efficiency compared to full melting. However, vacuum conditions produce highly porous structures with compromised mechanical strength. This inherent brittleness and reduced load-bearing capacity make SLS unsuitable for structural habitat elements.

SLM

Selective Laser Melting (SLM) fully liquefies regolith into a vitrified, glass-like solid, minimizing porosity for superior cohesion and compressive strength (up to 125 MPa at 1500°C). Though energy-intensive due to higher laser power, it outperforms SLS in structural integrity without binders. Porosity can be further reduced via elevated temperatures or a second laser pass to release trapped gases. SLM was selected for its balance of performance and ISRU reliance, enabling robust, monolithic habitats despite scalability needing vacuum multi-layer validation.

Concept selection

To evaluate the two concept a series of seven selection criteria where defined

- Technical Complexity: number of subsystems and the difficulty to implement them in the lunar environment

- Technological maturity and Risk: how much are the technologies involved in the concept developed and tested.

- Adaptability: measures how modular and scalable the design is

- Reliability and Maintenance: Measures the robustness of autonomous systems, their ability to continue functioning over time, and the ease of maintenance or replacement are therefore central considerations.

- Structural Integrity and Durability: The habitat must not only stand structurally once assembled but also be able to withstand the lunar environment for a long period of time. This includes resilience against radiation, micro-meteorite impacts, seismic vibrations, and extreme temperature cycles.

- Construction Time: Timely construction is important for mission planning and logistics. Assesses the total duration of the construction process, from regolith gathering to completion, and how effectively timelines can be accelerated by increasing the amount of construction equipment.

- Logistical Cost: Launching material from Earth is the main cost driver of any space mission. This criterion focuses on the total mass that needs to be shipped from Earth to realize the concept.

The seven criteria were assigned a weight using an Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP).

Based on the evaluation across all criteria, Concept 2 emerges as the more favorable option for the mission objectives. Its lower technical complexity, higher adaptability, ease of maintenance, and stronger structural resilience under lunar conditions make it better aligned with the long-term sustainability and operational requirements of constructing a habitat in a lava tube. A key factor in this decision is cost, which carries the highest weight in the evaluation. Given the relatively low public interest in space exploration since the end of the space race, it is of utmost importance to provide a solution that is as cost-efficient as possible. A lower-cost approach increases the likelihood of delivering meaningful results within the current Artemis program budget and helps justify public funding, while also providing the potential to renew public enthusiasm for lunar exploration. Even though some private interest exists, it is likely that the first approach mission will be primarily agency-funded, making budget constraints a critical consideration for both policymakers and the public. Concept 2 is advantageous in this regard because it reduces the need for heavy, expensive SLM machines and eliminates the logistical and operational complexity of transporting and precisely placing pre-fabricated blocks, as required in Concept 1. Instead, it relies on smaller, modular laser-equipped robots to perform in-situ regolith melting, achieving similar construction goals with potentially lower costs and greater flexibility. Despite these advantages, the feasibility of large-scale regolith laser melting remains the most critical open question. Interviews with several experts have demonstrated that this technology shows promise. However, many challenges still remain before it can be applied on a large scale in a real lunar environment. In summary, Concept 2 offers the best balance between technical feasibility, operational robustness, adapt ability, and cost-efficiency, making it the preferred choice for the mission. As a result, subsequent development efforts and mission planning will focus on this second concept

Final Design

The habitat is a catenary dome with 20 m inner diameter, 120 m² floor area, and 556 m³ volume suitable for three astronauts. Built around an inflatable substructure that forms the pressurized volume, the shell uses a gradient voronoi infill (25% at base decreasing to 5% at top, averaging 15%) for material efficiency, with a thin unmelted regolith buffer protecting the inflatable during SLM. In total, the volume of the shell of the habitat will be roughly 220 m3 , resulting in a total mass of around 330 tons, assuming an average regolith density of 1,5 g/cm3.

Melted regolith exhibits high compressive strength (18.4 MPa at a melting temperature of 1500°C) but lower tensile performance (16.3 MPa), necessitating the catenary shape to maintain loads primarily in compression while transferring part to the inflatable. For radiation protection, a minimum 54 cm wall thickness (with safety factor) reduces internal dose to below 10 mSv/y inside the lava tube, leveraging the natural shielding provided by constructing the habitat inside the lava tube, which lowers exposure by a factor of 40 compared to the surface.

Robotic Swarm

The final design employs a diverse robotic swarm to autonomously construct the habitat shell via in-situ SLM of regolith. The system encompasses material handling for collection, processing and deposition, additive manufacturing for layer fusion , and support infrastructure with charging stations.

Collector robot

The robot responsible for collecting lunar material outside of the lava tube is based on NASA’s IPEx concept. This 30 kg lightweight, battery-powered robot, equipped with two counterrotating drums, can collect and transport up to 30 kg of lunar regolith. This robot will also be used to precisely deposit the material required to construct each layer. Additionally, it will discard unusable material with a particle size > 2 mm at a designated location inside the lava tube.

Flattener robot

This robot, called the flattener, is a 25 kg battery-powered machine designed to prepare an even layer of fine regolith for the melting process. It spreads out the deposited piles of processed regolith (with particles < 2 mm) and flattens it into a uniform 10 mm thick layer. Operating at a capacity of 50 m²/h, it ensures every layer is perfectly flat and ready for melting.

Melting robot

The laser melting robot is based on the GITAI Rover R1.5 platform. It features a long-reach robotic arm (almost 2 meters) equipped with a 1,5 kW laser, which is guided from a back-mounted box via a fiber-optic cable. The robot utilizes a tethered power connection for energy-intensive melting tasks and uses batteries for other operations. Its design supports modular tools and can also be fitted with a manipulator arm for setup procedures.

Processing Machine

A pair of stationary processing machines, located inside the lava tube, receive raw regolith delivered by the collector robots. Using centrifugal sieves, they separate the material into a fine fraction (0-2 mm) suitable for SLM and a coarse fraction (>2 mm) to be discarded. Buffers on either side of the sieve maintain a steady supply chain, allowing continuous operation even if deliveries are intermittent.

Construction Process

The habitat’s assembly is a sequential, 15-step process, organized into two primary phases: the preparation mission (steps 1-6) and the construction mission (steps 7-15). The initial phase focuses on establishing the necessary power and site infrastructure, while the second phase executes the deployment and autonomous construction of the habitat itself.

Preparation Mission

Before construction of the habitat can begin, the site inside the lava tube must be prepared to ensure safe and efficient robotic operations. This phase starts with the deployment of fixed solar panels on the lunar surface near the lava tube entrance to capture sunlight and generate power. Power cables are then routed from these panels down into the tube, secured along the walls or floor to avoid interference with robot mobility. The power grid is tested for stability, including connections to wireless charging stations inside the tube that will keep the mobile robots operational. Next, the melting robots (equipped with removable scanning equipment) survey the designated build site. They map the terrain using onboard LiDAR and cameras to identify any irregularities, such as loose rocks or slopes. Assessment follows, evaluating floor flatness, ceiling height clearance for the final dome, and proximity to the entrance for material transport. If needed, the site is cleared: collector robots remove larger obstacles or excess loose regolith, transporting it to a waste area deeper in the tube. Finally, a detailed 3D digital twin of the site is created by scanning with high-precision instruments on the melting robots. This model serves as the reference for all subsequent construction planning, enabling precise layer deposition paths and real-time progress tracking against the catenary dome design.

Construction Mission

With preparation complete, the core building phase commences. The inflatable substructure is deployed by melting robots using their manipulator arms and inflated to form the pressurized volume and initial support scaffold. Anchors secure it to the lava tube floor for stability. Collector robots then begin harvesting regolith from the surface, transporting loads into the tube and dumping them at the processing machines. The machines sieve the material, the fine fractions are kept while coarse waste is collected and hauled away by the same collector robots to the designated internal dump site. For each 10 mm layer, collector robots deposit piles of fine regolith in calculated positions around the inflatable, following paths derived from the digital twin. The flattener robots then spread and level the material into a uniform layer ready for fusion. Multiple units work in parallel to cover the dome's circumference efficiently. Melting robots, tethered for power, then scan the prepared layer with their lasers, selectively melting the regolith according to the gradient voronoi infill pattern; denser at the base for structural support, sparser toward the top for material savings. An unmelted buffer layer is maintained closest to the inflatable to prevent heat damage. Parallel melting operations accelerate the process, with robots coordinating to avoid overlaps or gaps. Throughout, the swarm maintains the site by clearing dust kicked up during deposition or flattening, using collector robots for removal. Periodic inspections via IR cameras on melting robots verify layer integrity, with the digital twin updated after each cycle. This layer-by-layer additive process continues until the full shell thickness is achieved, culminating in a sealed, radiation-shielded habitat.

Power Generation

The power generation requirements are primarily driven by the laser system. The total construction system requires an average of ≈ 30kW of power. This is mainly due to the energy demand of the laser robots, which each consume approximately 4 kW; 3 kW for the laser operation itself and 1 kW for supporting systems and basic functionality.

The main power technologies traditionally used in space missions include solar arrays, fuel cells, and radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs). Solar arrays are lightweight and highly reliable, but their output is constrained by the lunar day and night cycle. Fuel cells can provide continuous power over shorter durations and were historically used in missions such as Apollo. RTGs, which convert radioactive decay heat into electricity, are widely used in deep-space missions where sunlight is scarce but are not suitable for missions that require big amounts of energy. More recently, renewed interest has turned toward compact nuclear fission reactors such as NASA’s Kilopower concept, which targets on the order of 10 kW per unit (Gibson and Oleson, 2017). Such systems could sustain robotic construction during the 14-day lunar night. However, their deployment is heavily constrained by regulatory concerns; in the event of launch failure, dispersal of nuclear material in the atmosphere and ocean remains a major risk. In this work, the selected baseline power architecture consists of solar arrays for power generation and batteries for energy storage. This choice prioritizes technological maturity, launch approval feasibility, and system reliability over the regulatory and risk barriers associated with nuclear systems. The dominant cost driver in such an architecture is the battery mass required to bridge the full duration of lunar nights while construction and excavation activities continue without interruption. Operating continuously through the entire 14-day night imposes a substantial storage requirement, whereas reducing or pausing activity during darkness could significantly decrease the needed battery mass and thus system cost.

Construction Time

A discrete-time simulation was developed to estimate the autonomous construction timeline, advancing second-by-second while modeling each robot as an agent with tracked battery levels, operational rates, states (working, traveling, charging, etc.), positions, loads, and maintenance. The process sequences through 380 layers, each requiring deposition, flattening, and melting phases in order, with parameters for 8 collectors, 3 depositors, 5 flatteners, 5 melters, processing at 150 kg/h (90% efficiency), and 8 charging stations under daytime-only operations (lunar nights impose hibernation, doubling calendar time). Results indicate approximately 6432 active hours (268 days) for productive work, extending to 1.48 calendar years when including night downtimes. Every layer requires roughly 17 hours to construct, with melting dominating (~68% of time), followed by deposition (~20%) and flattening (~12%); higher layers require less time due to reducing dome area.

Recommendations for Future Work

Future efforts should prioritize experimental validation of large-scale, multi-layer SLM in lunar-like vacuum conditions to confirm adhesion, porosity reduction (potentially via double-pass melting), and mechanical integrity of the monolithic structure, alongside sieving tests with diverse regolith simulants to verify 90% yield for <2 mm fractions. Structural modeling must address moonquake resilience up to magnitude 5.7, refining the catenary dome and voronoi infill for vitreous material fragility, while exploring alternative geometries and modular connections for expanded complexes.

Mission architecture expansion should detail preparation phases and evaluate alternative power sources such as nuclear to enable continuous construction operations. This eliminates the need for hibernation periods during the lunar night, which can shorten timelines, and reduce long-term battery costs. However, while reducing night-time power usage to 1 kW is feasible during the robotic construction process, subsequent human habitation demands higher sustained power levels, making such drastic power limitation unfeasible post-construction.

Conclusion

This project has delivered a viable conceptual design for autonomously constructing a permanent lunar habitat inside a lava tube using in-situ SLM of regolith, overcoming key barriers to sustainable human presence on the Moon. By selecting the layer-by-layer in-situ melting approach over prefabricated blocks, the design achieves superior logistical efficiency, adaptability, and structural integrity tailored to the lava tube's protective environment. The 20 m catenary dome, with 556 m³ volume, gradient voronoi infill, and 54 cm melted-regolith shell, meets radiation limits (<10 mSv/y) and leverages compressive strengths (~125 MPa at 1500°C) while accommodating tensile limitations through shape and inflatable load-sharing. The robotic swarm of collectors/depositors, flatteners, and melters, executes the 15-step process fully autonomously. Preparation establishes solar infrastructure and a site digital twin; construction deploys the inflatable, processes ~327 tons of fine regolith, and builds layer-by-layer within 2 years under daytime-only operations.

Daytime-only operation improves economic feasibility by minimizing battery mass (1,553 kg vs. 70,358 kg continuous), resulting in a total mission cost of €7.3 billion, a reduction of 90% compared to the continuous operations baseline, at the cost of doubling the total construction timeline. Construction of the habitat inside a lava tube reduces shielding needs (40× reduction compared to the surface), but moonquakes remain a big concern.

SLM shows promise as a technology to use for the construction of the habitat, but future validation must prioritize large scale SLM performance in lunar conditions. Further research must be conducted regarding sieving yields, and moonquake-resilient modeling. Developing detailed robotic prototypes, advanced swarm coordination simulations, robust hibernation and dust-mitigation protocols, and investigating nuclear power for continuous operations, thereby shortening the construction timeline and supporting sustained crewed habitation, are all critical steps to advance from conceptual design to real-world deployment, ultimately enabling cost-effective, ISRU-maximized lunar settlement.

Documents

Reports

Final Report: [PDF]

Midterm Report: [PDF]

Problem Statement Report: [PDF]

Presentations

Final Presentation: [PPTX] [PDF]

Midterm Presentation: [PPTX] [PDF]

Problem Statement Presentation: [PPTX] [PDF]

Public Poster Presentation [PDF]